Meaning of Market

A market is a place or system where buyers and sellers come into contact to exchange goods and services, facilitating transactions between those who want to buy and those who want to sell.

Classification of Markets

Markets can be classified in several ways, based on factors such as geographical area, time, and competition level. Below are the main classifications:

(a) On the Basis of Area or Locality: Markets can be classified into three types based on the geographical area in which goods are exchanged:

- Local Market: A local market refers to a market where a particular commodity is exchanged within a limited geographical area, typically where the commodity is produced. For example, vegetables, flowers, and fruits are often sold in the area where they are grown.

- National Market: A national market is one where goods are bought and sold across the country. Commodities like wheat, sugar, and cotton, which are produced and consumed in various parts of the country, fall under the national market.

- International Market: An international market involves the exchange of goods and services across national borders. Examples include markets for gold, silver, wheat, and cotton.

(b) On the Basis of Time Element: Markets can also be classified based on the duration of market conditions and the period under consideration:

- Very Short Period Market: In a very short period market, the supply of goods cannot be increased because producers lack the time to adjust production. These markets are typically influenced by temporary conditions, such as seasonal demand or shortages.

- Short Period Market: In a short-period market, producers can make some adjustments to supply, but not enough to fully respond to changes in demand. For example, in agriculture, farmers can adjust production in the short term but may be limited by existing crop cycles.

- Long Period Market: In a long-period market, firms have sufficient time to adjust factors of production, including labor and capital, to meet changes in demand. This adjustment allows the market to achieve a more stable equilibrium over time.

(c) On the Basis of Competition Among Sellers: Markets can be classified based on the level of competition among sellers or producers, divided into two main types:

-

Perfect Competition Market: A market is perfectly competitive when there are many buyers and sellers, and no single seller can control the price of the product. In perfect competition, products are homogeneous (identical), and information is freely available to all participants. Although examples of perfect competition are rare, agricultural markets often exhibit some characteristics of perfect competition.

-

Imperfect Competition Market: In an imperfect competition market, there are fewer sellers or producers, each with some control over product prices. Products in such markets are differentiated by quality, features, or branding. Types of imperfect competition include monopoly, monopolistic competition, and oligopoly.

Perfect Competition

The more nearly perfect a market is, the stronger the tendency for the same price to be paid for the same good in all parts of the market." - Alfred Marshall

Features of a Perfect Market

A perfectly competitive market has the following characteristics:

- Large Number of Sellers and Buyers: In a perfectly competitive market, many buyers and sellers participate, with each representing only a small portion of the total market. No single producer or consumer can influence the price, which is determined by overall supply and demand. Each participant is a price taker, meaning they accept the market price without trying to influence it.

- Homogeneous Commodities: The goods offered in this market are identical in every way. Consumers can buy the same product from any seller and receive consistent quality. This uniformity ensures a single price for the good throughout the market, as consumers will naturally purchase from the seller with the best price.

- Free Entry and Exit: Firms can freely enter or exit the market. If firms can earn supernormal profits, new firms will enter, increasing supply and lowering prices back to the normal profit level. Conversely, if firms incur losses, they will exit, reducing supply and driving prices back up. This process ensures that, in the long run, firms in a perfectly competitive market earn only normal profits.

- Mobility of Factors of Production: Factors of production (land, labor, capital) can move easily between industries. When firms in one industry offer higher returns, resources shift toward that industry, ensuring factors are allocated efficiently to their most productive uses.

- Absence of Transport Costs: In a perfectly competitive market, there are no transport costs. If transport costs existed, prices of goods would differ between local and distant markets, violating the condition of perfect competition, which requires a uniform price for the same product across the market.

- Perfect Knowledge of the Market: All buyers and sellers have complete information, knowing the price, quality, and availability of products across the market. With perfect knowledge, transactions occur at a single price, as no individual can charge more than the market price without losing customers to other sellers offering the same product at a lower price.

Price Determination

In a perfectly competitive market, price is determined by market forces—specifically, the interaction between supply and demand. The market establishes a balance between the quantity of goods available for sale and the quantity demanded by consumers. This balance is known as the equilibrium price, which is set at the point where the quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded.

Changes in supply and demand directly affect the equilibrium price. If demand increases or supply decreases, the equilibrium price will rise. Conversely, if demand decreases or supply increases, the equilibrium price will fall.

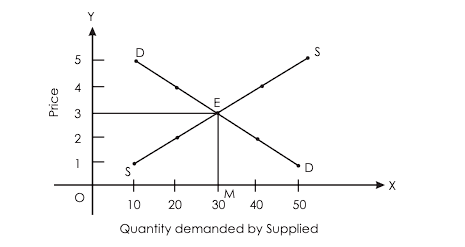

The table below illustrates the relationship between price, quantity demanded, and quantity supplied:

| Price | Quantity Demanded | Quantity Supplied |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | 10 |

| 2 | 40 | 20 |

| 3 | 30 | 30 |

| 4 | 20 | 40 |

| 5 | 10 | 50 |

In this table:

- Price 3 represents the equilibrium price, where the quantity demanded (30) equals the quantity supplied (30).

- At prices above 3 (e.g., Price 4 or 5), supply exceeds demand, leading to a surplus.

- At prices below 3 (e.g., Price 1 or 2), demand exceeds supply, leading to a shortage.

Thus, equilibrium occurs when supply and demand are equal, and this price is where market forces stabilize.

Explanation of the Diagram: In the diagram:

- The OX-axis represents the quantity of the good.

- The OY-axis represents the price of the good.

- DD is the demand curve, which shows the quantity demanded at various prices.

- SS is the supply curve, indicating the quantity supplied at different prices.

- Both curves intersect at point E, the equilibrium point. The price where demand equals supply is called the equilibrium price, denoted as OP in the diagram, and the corresponding quantity is labeled OM. At this equilibrium price and quantity, demand and supply are balanced, meaning there is no shortage or surplus of the good.

Imperfect Competition Market: Imperfect competition appears in several forms, including:

- Monopoly

- Duopoly

- Oligopoly

- Monopolistic competition

Monopoly Market

The term "monopoly" is derived from two Greek words: "Mono," meaning single, and "Poly," meaning seller. A monopoly market exists when there is only one seller or producer. This single seller supplies the entire market, and the monopolist’s product has no close substitutes. Significant barriers prevent other producers from entering the market, resulting in a lack of competition.

Features of a Monopoly: A monopoly market has the following features:

- Single Firm: Only one firm produces the commodity in the market; there is only one seller or producer.

- No Close Substitutes: The monopolist’s product has no close substitutes, so consumers have no alternative choices for similar goods.

- Strong Barriers to Entry: High barriers to entry, such as large capital requirements, technological constraints, patents, or government regulations, prevent new firms from entering the market.

- Firm and Industry Are the Same: Since only one firm exists in a monopoly market, the firm and the industry are essentially synonymous.

- Price Maker: In a monopoly market, the monopolist acts as a price maker, setting the price of the product due to the absence of competitors.

- Nature of AR & MR Curves: The Average Revenue (AR) and Marginal Revenue (MR) curves both slope downward from left to right. To sell more output, the monopolist must lower the price, causing both AR and MR to decline.

- Price Discrimination: The monopolist can practice price discrimination, charging different prices to different customers for the same product or service. Unlike in a perfectly competitive market, prices are not uniform.

- Profit Maximization: The primary objective of a monopolist is to maximize profits.

Price and Output Determination in a Monopoly Market

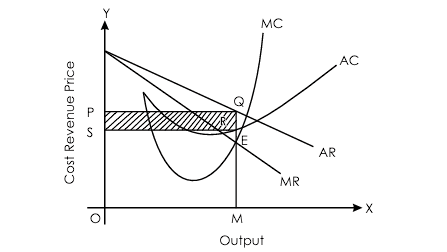

In a monopoly market, the monopolist can control either the price of the commodity or the quantity supplied, but not both simultaneously. The monopolist may raise the price by reducing output or increase sales volume by lowering the price. The monopolist's primary objective is to maximize profits. This is illustrated in the diagram below:

In the diagram:

- The OX-axis represents output, while the OY-axis represents cost, revenue, and price.

- MR denotes the marginal revenue curve, and MC is the marginal cost curve. These two curves intersect at point E, which represents the equilibrium level of output, OM.

- At this output level, average revenue (AR) is denoted by point Q. The price is shown as OP, and the average cost as OS. Since AR > AC, the monopolist earns maximum profits.

Abnormal Profits =

=

=

=

Monopolistic Competition Market

The concept of monopolistic competition was introduced by Professor Edward Chamberlin. This market structure features many sellers offering similar but not identical products. It combines elements of both monopoly and perfect competition, hence the name monopolistic competition. Industries such as cosmetics, soaps, and other consumer goods often exhibit this structure.

Characteristics of Monopolistic Competition

- Considerable Number of Producers: Many producers exist in the market, yet no single producer has control over the total market output. High competition is common among producers.

- Product Differentiation: Products are differentiated by each producer through characteristics like material, color, design, fragrance, packaging, trademarks, etc. This differentiation gives each product a unique identity in the market.

- Free Entry and Exit: Firms can freely enter or exit the market. High profits attract new firms, while losses drive inefficient firms out, maintaining a competitive environment.

- Selling Costs: Firms incur significant expenses to promote their products. These selling costs include advertising in newspapers, journals, electronic media, and promotional activities like exhibitions and free samples.

- Imperfect Knowledge: Buyers often have limited knowledge about the market's products, and advertising can lead them to perceive similar products as distinct or even superior to others.

- Price Decision Power: Each firm offers a slightly differentiated product, allowing it some control over its pricing. Consequently, each firm’s demand curve is downward-sloping, with a higher price elasticity of demand than in monopoly markets.

Price and Output Determination under Monopolistic Competition

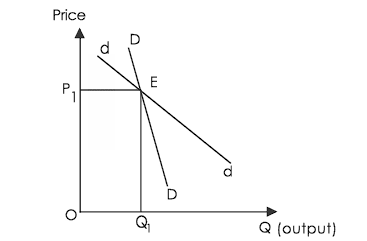

In a monopolistic competition market, two types of demand curves can be identified:

- Perceived Demand Curve

- Proportional Demand Curve

Perceived Demand Curve:

The perceived demand curve shows various combinations of price and quantity demanded where the firm feels no incentive to adjust its output or price. This curve reflects the firm’s perception of how much it can sell at different prices, assuming competitor prices remain constant.

Proportional Demand Curve:

The proportional demand curve illustrates the impact when all firms in the market simultaneously change their prices. It represents the shift in market demand that occurs as rival firms respond to each other's price adjustments.

The price in a monopolistic competition market is determined at the intersection of the perceived demand curve (dd) and the proportional demand curve (DD).

Duopoly Market

A duopoly market is a specific type of oligopoly where only two producers or firms dominate the market. The decisions of each firm regarding pricing, production, and strategy can significantly impact the other, leading to a high level of interdependence.

Oligopoly Market

The term "oligopoly" is derived from two Greek words: oligo (meaning "few") and pollien (meaning "sellers"). In an oligopoly market, only a few firms, producers, or sellers control a large portion of the total market output. Typical examples of oligopoly markets include the automobile, gas, and cigarette industries.

In an oligopoly, firms can produce homogeneous or differentiated products. With few producers, each firm commands a significant share of the market, enabling them to influence market outcomes. Competition exists among these dominant firms, making the market structure distinct from both monopoly and perfect competition.

Key Features of Oligopoly

1. Small Number of Firms:

The number of firms in an oligopoly is limited, often around five or fewer, with each firm controlling a substantial portion of the total market output. Due to this concentration, each firm can influence the market by adjusting its output, which in turn affects the market price.

2. Interdependence:

The actions of one firm affect the others, creating a high level of interdependence. Since each firm produces a large share of the market’s output, any change in price or output by one firm often prompts strategic responses from competitors.

3. Selling Costs:

Firms in an oligopoly spend heavily on advertising and brand promotion to differentiate their products and attract customers. This includes advertising, promotional offers, and brand-building campaigns aimed at customer loyalty and market share retention.

4. Uncertainty:

Due to interdependent decision-making, firms in an oligopoly face uncertainty. Each firm’s pricing and output decisions are influenced by anticipated reactions from competitors, making it challenging to predict future price and output levels.

5. Price Rigidity:

Prices in an oligopoly market tend to be stable. Firms avoid frequent price changes due to potential price wars. If one firm raises its price, others may not follow, risking a loss of market share for the price-raising firm. Conversely, price cuts are often matched by competitors, leading to potential price wars. This tendency to keep prices stable is known as price rigidity.

Price and Output Determination Models in Oligopoly

1. Cournot’s Model:

In this model, each firm assumes that its rival will maintain its current output level regardless of its own actions. As a result, the equilibrium output in a Cournot duopoly is two-thirds of the competitive output level, and the price is two-thirds of the monopoly price.

2. Stackelberg Model:

The Stackelberg model incorporates a leader-follower dynamic where one firm (the leader) makes its output decision first, and the other firm (the follower) responds. The leader typically earns higher profits by setting its output advantageously before the follower.

3. Bertrand Model:

In the Bertrand model, firms compete by setting prices rather than output levels. Price competition continues until prices equal marginal costs, leading to a highly competitive scenario similar to perfect competition.

4. Edgeworth Model:

Edgeworth’s model assumes each firm believes its competitor will maintain current prices. This results in no fixed equilibrium, as firms constantly adjust prices based on each other's responses, leading to potential price fluctuations and instability.

5. Collusive Oligopoly:

In a collusive oligopoly, firms cooperate to fix prices or output levels, maximizing joint profits. Such collusion, often illegal, is exemplified by cartels like OPEC, where member countries regulate oil production to influence prices.

Common Pricing Strategies in Oligopoly

1. Cost-Plus Pricing:

Firms calculate production costs and add a markup to ensure profit, covering costs with a consistent profit margin.

2. Limit Pricing:

To deter new entrants, a firm sets prices below monopoly levels, making it difficult for newcomers to compete profitably.

3. Penetration Pricing:

This strategy involves setting an initially low price to attract customers and gain market share quickly. Prices may later increase once customer loyalty is established.

4. Price Discrimination:

Oligopolists may charge different prices for the same product based on customer segments, like charging higher rates for business versus economy class in airlines.

5. Psychological Pricing:

Pricing products just below whole numbers (e.g., ₹3.99 instead of ₹4.00) appeals to consumer psychology, making prices appear lower.

6. Dynamic Pricing:

Dynamic pricing allows for flexible price adjustments based on demand or market conditions. This is commonly used in industries such as airlines and e-commerce.

7. Price Leadership:

In some oligopolies, a dominant firm sets prices that others follow. The leading firm, or price leader, generally has significant market influence.

8. Target Pricing:

Firms set prices to achieve a specific rate of return on investment. Often used by companies with high capital investments, like utilities and automotive manufacturers.

9. Absorption Pricing:

All production costs are included in the product’s price, covering both variable and fixed costs, ensuring full cost recovery.

10. High-Low Pricing:

Firms set generally high prices but offer periodic discounts or promotions to attract budget-conscious consumers while maintaining higher profit margins on regular sales.

11. Marginal-Cost Pricing:

The firm sets prices at the marginal cost of producing one additional unit, which is often done to cover variable costs without covering total costs, especially in industries with excess capacity.